How to Prevent Spring Allergies

Now that spring has sprung, retail clinicians are likely seeing an influx of patients reporting seasonal allergy symptoms.

Now that spring has sprung, retail clinicians are likely seeing an influx of patients reporting seasonal allergy symptoms. Spring allergies, or allergic rhinitis (AR), affect 10% to 30% of the US population each year,1impacting quality of life and the ability to function productively in work and school. Although intranasal corticosteroids can treat these symptoms effectively,2it is better to prevent symptoms before they arise. This article reviews the pathogenesis, risk factors, epidemiology, assessment, diagnosis, and preventive treatment for AR.

Overview

AR is a common, chronic disorder that affects the respiratory tract.2Also known as hay fever, pollinosis, and allergic rhinosinusitis, the condition often follows a temporal pattern in response to the following season-related allergens2:

- Grass (timothy and Bermuda)

- Weeds (ragweed)

- Outdoor mold spores (Alternaria, Aspergillus, and Cladosporium)

- Trees (birch, oak, maple, and mountain cedar)

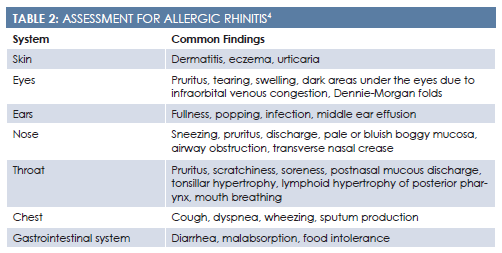

Patients with AR typically arrive at the retail clinic with sneezing, itching, nasal congestion, and rhinorrhea. Their nasal mucosa will appear bluish, boggy, pale, and enlarged. Other signs include dark patches under the eyes from venous congestion, nasal crease, nasal polyps, and cobblestoning of the posterior oropharynx due to postnasal drip.2

Pathogenesis

Allergy symptoms arise due to an immunoglobulin— mediated response and mast cell histamine release. Histamine results in vasodilation, plasma exudation, and mucus production,3and these triggers create the previously noted traditional presenting symptoms. Allergic inflammation develops within minutes of exposure and peaks 15 to 30 minutes later.3

Risk Factors

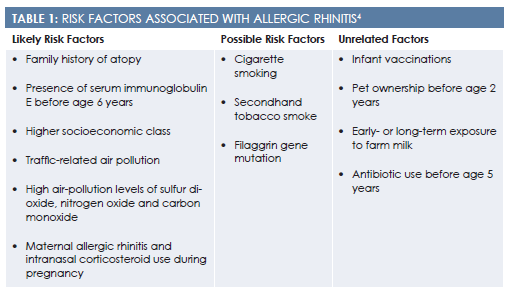

Risk factors for developing AR include a family history of atopy, higher socioeconomic class, and residence in an urban area (Table 14). Although no definitive evidence exists, tobacco smoke may also increase an individual’s risk. Despite popular belief, infant vaccinations and pet ownership are not associated with an increased risk.4

Epidemiology

Seasonal allergy is the 12th most common diagnosis made by primary care providers.5Since the 1960s, the rate of AR has continued to rise so fast that genetic factors are unlikely to be causative. Instead, changes in home ventilation, a decline in physical activity, and alterations in diet have increased the number of people suffering from allergic diseases.6The Natural Resources Defense Council also points to increased ozone smog and excessive ragweed pollen due to global warming as possible factors.7

Assessment and Diagnosis

Nurse practitioners and physician assistants diagnose AR based on the patient’s presentation, history, and exposure to allergens. The patient’s chief complaint will likely encompass sneezing, copious rhinorrhea, and persistent nasal congestion. Upon further questioning, clinicians may find additional related symptoms, such as postnasal drip, impaired sense of taste and smell, persistent cough, malaise, epistaxis, and nasal polyps.2

While obtaining the patient’s history of present illness, primary care provider should ask about the following4:

- Pattern and duration of nasal symptoms

- Environmental history

- Precipitating factors such as known allergens

- Coexisting conditions, such as asthma, sleep apnea, sinusitis, otitis media, and allergic conjunctivitis

The patient’s family history should be assessed for an atopic disorder, chronic sinus issues, and recurrent bronchitis. The patient also should be asked about the possible presence of mold and water damage in the home, occupational exposure to allergens, and tobacco use.4During the review of systems, it may be helpful to include the symptoms’ effects on the patient’s quality of life in addition to standard assessment questions (Table 24).

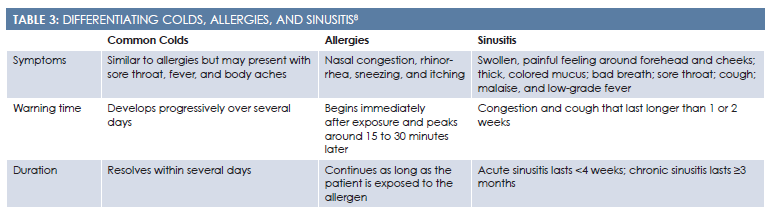

The differential diagnosis should include nonallergic rhinitis syndromes, such as vasomotor, gustatory, atrophic, and drug-induced rhinitis (Table 38). The clinician should suspect a nonallergic cause if the patient presents with fever, cervical adenopathy, and purulent nasal discharge. A physical obstruction (eg, septal deviation, tumors, foreign body) can also cause symptoms that mimic AR. Other causes of abnormal nasal function include cystic fibrosis, primary ciliary dyskinesia, vasculitis, and cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea.2

Preventive Measures

Treating AR involves a holistic approach: allergen avoidance, medication, nasal saline irrigation, and complementary therapies, such as butterbur supplements and acupuncture.4Results of newer research have also shown a link between adherence to a Mediterranean diet in childhood and reduced risk for AR.9

Allergen Avoidance

Avoiding allergen triggers can help minimize symptoms. Patients who are sensitive to spring pollen should be instructed to keep their house and car windows closed, stay inside on high-pollen days, never dry clothes outside, and shower before bed.4Patients might benefit from downloading an allergy alert app for their smartphone in order to receive daily weather and allergy forecasts. The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology’s National Allergy Bureau (aaaai.org/global/nab-pollen-counts) also publishes accurate pollen and mold levels across different regions of the United States.

If patients must go outside on high-pollen days, they should be encouraged to wear a mask or nasal filter, which can be purchased at a local pharmacy. Because pollen is most concentrated in the air during the early morning, patients should wait until midday to go outside, if possible. They should change their clothing whenever possible because pollen often clings to fabric long after the initial exposure. Patients should also vacuum their home and car frequently during allergy season to pick up excess pollen that has accumulated on the floor.4

Medication

Intranasal corticosteroids are the treatment of choice for AR (Table 410).2The Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology has published the following recommendations for medication use in treating seasonal allergies2:

- Intranasal corticosteroids are the most effective medications for managing seasonal allergies.

- Intranasal corticosteroids appear to be more effective when combined with an antihistamine and leukotriene antagonist.

- Although these medications can be taken as needed, research demonstrates that they are more effective when taken continuously through allergy season.

- No evidence suggests that 1 corticosteroid brand is better than another.

- Budesonide may be the preferred medication to use during pregnancy (Category B).

These medications are not associated with any major adverse effects or systemic side effects. Minimal local side effects may include intraocular pressure, nasal irrigation, and nosebleeds. The known incidence of nosebleeds per medication is included inTable 410.

Table 4: Intranasal Corticosteroid Dosing10

Medication

Dose

Instructions

Incidence of Nosebleeds

Beclomethasone dipropionate

42 mcg

1—2 sprays in each nostril twice daily for patients aged ≥6 years

<3%

Budesonide

32 mcg

1—4 sprays in each nostril once daily for patients aged ≥6 years; 1–2 sprays once daily for patients aged 6–11 years

8% vs a placebo rate of 5%

Ciclesonide

50 mcg

2 sprays in each nostril once daily for patients aged ≥6 years; only approved for seasonal allergic rhinitis in children aged 6—11 years

Unknown

Flunisolide

250 mcg

2 sprays in each nostril 2—3 times daily, 1 spray in each nostril 3 times daily, or 2 sprays in each nostril twice daily for patients aged 6–14 years

3%—9%

Fluticasone furoate

27.5 mcg

2 sprays in each nostril once daily; 1 spray in each nostril once daily for patients aged 2—11 years

Unknown

Fluticasone propionate

50 mcg

1—2 sprays in each nostril once daily or 1 spray in each nostril twice daily; 1–2 sprays in each nostril once daily for patients aged 4–11 years

6%—7% vs a placebo rate of 5.4%

Mometasone furoate

50 mcg

2 sprays in each nostril once daily; 1 spray in each nostril once daily for patients aged 2—11 years

8%—11% vs a placebo rate of 6%-9%

Triamcinolone acetonide

55 mcg

1—2 sprays in each nostril once daily for patients aged ≥6 years

2.7% vs a placebo rate of 0.8%

Nasal Saline Irrigation

Research demonstrates that nasal irrigation with mildly alkaline saline can improve AR symptoms in both adults and children. Results from a 2007 systematic review found nasal irrigation to be effective, although not as effective as an intranasal corticosteroid.11Nasal irrigation is often the treatment of choice for women who are pregnant and wish to avoid medications. Patients should be instructed to clean their nasal saline irrigation devices regularly with distilled or boiled water to reduce the risk for contamination, especially from the amoebaNaegleria fowleri.4

Butterbur

Butterbur is an OTC supplement used to treat AR. Its scientific name isPetasites hybridus, and it is also called blatterdock, bog rhubarb, bogshorns, butterdock, butterfly dock, capdockin, flapperdock, langwort, or umbrella leaves. Strong evidence suggests that this supplement can reduce symptoms of seasonal allergies. Patients should never consume unprocessed plant forms of butterbur, and they should always purchase unsaturated pyrrolizidine alkaloid—free formulations.4The following are manufacturer-recommended doses4:

- Petaforce: 25-50 mg 2-3 times daily

- Petadolex: 25-75 mg 2-3 times daily, maximum 150 mg/day in adults, 50 mg/day in children

- Tesalin (Ze 339): 1-2 tablets 2-3 times daily

Acupuncture

Research results related to the effectiveness of acupuncture for treating AR are inconsistent. A 2009 systematic review of 12 randomized controlled trials found that acupuncture was associated with an overall reduction in average nasal symptom scores in 1801 patients.12On the other hand, results from a 2006 systematic review failed to show any measurable effects.13Results of a more recent study found that acupuncture improved quality of life for patients diagnosed with seasonal allergies.14The participants in this study received acupuncture 3 times a week for 4 weeks.

Mediterranean Diet

A 2007 cross-sectional study in rural Crete, Greece, examined the effects of a Mediterranean diet on childhood AR. The Mediterranean diet traditionally includes increased intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and olive oil. The researchers examined the diets of 690 children aged 7 to 18 years and then tested each child for 10 common allergens with skin prick tests. Results of this study showed that the Mediterranean diet protected children from developing allergies, although additional studies are needed to verify these findings.9

Conclusion

Every spring, AR affects up to 30% of the US population.1A variety of preventive measures can reduce the severity of rhinitis symptoms, including allergen avoidance, medication, nasal saline irrigation, butterbur supplementation, and acupuncture.4Educating your patients on the best management strategies can improve their quality of life during this spring season.

Dr. Melissa DeCapuais a board-certified psychiatric nurse practitioner. She works as a consultant for small health care technology companies, and she recently won the Seattle Health Innovator award. Dr. DeCapua is a strong advocate for empowering nurses, and she fiercely believes that nurses should play a pivotal role in shaping modern health care. For more about Dr. DeCapua, visit her website at melissadecapua. com and follow her on Twitter @ melissadecapua.

References

- Settipane RA. Demographics and epidemiology of allergic and nonallergic rhinitis.Allergy Asthma Proc2001;22(4):185-189.

- Wallace DV, Dykewicz MS, Bernstein DI, et al. The diagnosis and management of rhinitis: an updated practice parameter.J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(2 Suppl):S1-84. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.06.003.

- Min YG. The pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of allergic rhinitis.Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2010;2(2):65-76. doi: 10.4168/aair.2010.2.2.65

- Allergic rhinitis. DynaMed Plus website [database online]. EBSCO Information Services. dynamed.com/login.aspx?direct=true&site=DynaMed&id=113862. Updated March 1, 2015. Accessed February 19, 2016.

- Pace WD, Dickinson LM, Staton EW. Seasonal variation in diagnoses and visits to family physicians.Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(5):411-417.

- Sly RM. Changing prevalence of allergic rhinitis and asthma.Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1999;82(3):233-248.

- Declet-Barreto J, Alcorn S.Sneezing and Wheezing: How Climate Change Could Increase Ragweed Allergies, Air Pollution, and Asthma. New York, NY: Natural Resources Defense Council; 2015.

- American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Colds, allergies, and sinusitis: how to tell the difference. www.aaaai.org/Aaaai/media/MediaLibrary/PDF%20Documents/Libraries/EL-allergies-colds-allergies-sinusitis-patient.pdf. Published March 2012. Accessed March 11, 2016.

- Chatzi L, Apostolaki G, Bibakis I, et al. Protective effect of fruits, vegetables and the Mediterranean diet on asthma and allergies among children in Crete.Thorax.2007;62(8):677-683.

- Chisholm-Burns S, Schwinghammer T, Wells B, Malone P, DiPiro J.Pharmacotherapy Principles and Practice.3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2013.

- Harvey R, Hannan SA, Badia L, Scadding G. Nasal saline irrigations for the symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis.Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;18(3):CD006394.

- Lee MS, Pittler MH, Shin BC, Kim JI, Ernst E. Acupuncture for allergic rhinitis: a systematic review.Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102(4):269-279. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60330-4.

- Passalacqua G, Bousquet PJ, Carlsen KH, et al. ARIA update: I—Systematic review of complementary and alternative medicine for rhinitis and asthma.J Allergy Clin Immunol.2006;117(5):1054-1062. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2005.12.1308

- Xue CC, Zhang AL, Zhang CS, DaCosta C, Story DF, Thien FC. Acupuncture for seasonal allergic rhinitis: a randomized controlled trial.Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115(4):317-324e1. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.05.017.

Knock Out Aches and Pains From Cold

October 30th 2019The symptoms associated with colds, most commonly congestion, coughing, sneezing, and sore throats, are the body's response when a virus exerts its effects on the immune system. Cold symptoms peak at about 1 to 2 days and last 7 to 10 days but can last up to 3 weeks.

COPD: Should a Clinician Treat or Refer?

October 27th 2019The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) defines the condition as follows: “COPD is a common, preventable, and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that is due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases.â€

Diabetic Ketoacidosis Is Preventable With Proper Treatment

October 24th 2019Cancer, diabetes, and heart disease account for a large portion of the $3.3 trillion annual US health care expenditures. In fact, 90% of these expenditures are due to chronic conditions. About 23 million people in the United States have diabetes, 7 million have undiagnosed diabetes, and 83 million have prediabetes.

What Are the Latest Influenza Vaccine Recommendations?

October 21st 2019Clinicians should recommend routine yearly influenza vaccinations for everyone 6 months or older who has no contraindications for the 2019-2020 influenza season starting at the end of October, according to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

What Is the Best Way to Treat Pharyngitis?

October 18th 2019There are many different causes of throat discomfort, but patients commonly associate a sore throat with an infection and may think that they need antibiotics. This unfortunately leads to unnecessary antibiotic prescribing when clinicians do not apply evidence-based practice.