Counseling Pearls for IBS Patients

Irritable bowel syndrome is the most frequently diagnosed gastrointestinal (GI) disorder by primary care clinicians.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the most frequently diagnosed gastrointestinal (GI) disorder by primary care clinicians. With proper treatment, IBS can be managed and symptoms can be mitigated. Unfortunately, a recent survey found that patients often disagree with their primary care providers on both the etiology of their condition and appropriate treatment.1This article reviews best practices for managing IBS in the retail clinic setting and for counseling patients with this condition.

Epidemiology

IBS is a GI disorder with chronic and recurring abdominal pain and altered bowel habits.2This syndrome primarily affects women aged 20 to 30 years.3Worldwide, IBS affects approximately 14% of women and 9% of men; in North America, however, the prevalence increases to 16% in women and 10% in men.3For each individual, IBS symptoms fluctuate over time. Results of a survey of 1200 adults with IBS showed that 55% continued to have symptoms after 7 years.4Severe, chronic life stress accounts for 97% of the variance in IBS symptom duration and severity.5

Signs and Symptoms

IBS is classified as a functional GI disorder with abdominal pain and distention in the absence of specific organic pathology. Patients typically describe their abdominal pain as diffuse without radiation, located in the left lower quadrant, and triggered by food.6Additional altered bowel habits may include (1) constipation with hard, narrow stools intractable to laxatives; (2) diarrhea in small volumes of loose stool preceded by urgency of defecation; or (3) an alternation between constipation and diarrhea.7Other commonly reported symptoms include clear mucorrhea, dyspepsia, nausea, sexual dysfunction, and urinary frequency. Women may also express worsening of symptoms during the perimenstrual period.6

Retail clinicians should be on the lookout for the following signs and symptoms that are inconsistent with IBS, which suggest an organic pathology and require further evaluation6:

- Onset in middle age or older

- Acute symptoms

- Progressive symptoms

- Nocturnal symptoms

- Anorexia

- Weight loss

- Fever

- Rectal bleeding

- Painless diarrhea

- Steatorrhea

Assessment

A comprehensive history and physical examination should help the retail clinician make a correct diagnosis of IBS. The American College of Gastroenterology does not recommend laboratory testing or diagnostic imaging in patients with a typical IBS presentation if they are younger than 50, unless the following signs and symptoms are present: weight loss, iron deficiency anemia, or a family history of inflammatory bowel disease, celiac sprue, or colorectal cancer.8

Diagnosis

Retail clinicians may use the Rome III criteria to diagnosis IBS. These criteria state that patients must have experienced abdominal pain or discomfort for at least 3 days per month during the previous 3 months and at least 2 additional symptoms as listed above.9Retail clinicians may choose to note a bowel pattern, including diarrhea predominant, constipation predominant, mixed diarrhea and constipation, or alternating diarrhea and constipation.7

Treatment

IBS management consists of providing the patient with psychological support and recommending dietary measures. Pharmacologic management is not recommended, but it can be used to mitigate certain symptoms.8Retail clinicians should educate patients on the chronicity of IBS and reassure them that there is no underlying organic pathology.8 Successful treatment relies on a solid, trusting patient—provider relationship.

General Dietary Advice

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence encourages clinicians to offer general dietary advice and reassurance to their patients as first-line treatment for IBS.2This counseling should include the following recommendations2:

- Eat regularly and at the same times every day.

- Eat meals slowly.

- Drink at least 8 cups of water or other noncaffeinated drinks daily.

- Limit caffeinated tea and coffee to 3 cups per day.

- Limit fresh fruit intake to less than 240 g per day.

- Incorporate 1 tablespoon of oats or linseeds into meals per day.

- Avoid sorbitol.

Bulking Agents

Retail clinicians may recommend increased consumption of soluble fibers found in foods such as ispaghula or oats, as well as insoluble fibers found in food such as bran.2Fiber supplementation may also help some patients. Retail clinicians should be careful about which supplement they recommend, as some can exacerbate abdominal pain and distention. Specifically, polycarbophil compounds (Citrucel, FiberCon) may produce less flatulence than psyllium compounds (Metamucil).10Unfortunately, research on increased fiber intake is controversial because up to 70% of patients in fiber studies respond to placebo.10In addition, a recentCochranereview found no benefit in fiber supplementation for treating IBS.10

Probiotics

Researchers have yet to determine what form, dose, combination, or strain of probiotics is helpful in treating IBS.11Results from a recent meta-analysis recommend theBifidobacterium infantisstrain12; however, results from a different meta-analysis were inconclusive.13Overall, probiotics seem to be helpful in reducing pain, bloating, and gas, but the specific brand and dose remain unclear.

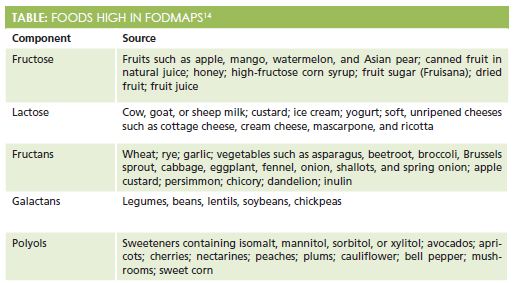

For patients interested in specific dietary modifications, retail clinicians should recommend the low FODMAP diet. The acronym FODMAP stands for fermentable oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides and polyols, which are specific carbohydrates found in foods. As osmotic carbohydrates, FODMAPs pull water into the intestinal tract and are difficult to digest, leading to symptoms of bloating, pain, and flatulance.14 FODMAPs include fructose, lactose, fructans, galactans, and polyols (Table14). Retail clinicians may recommend that patients avoid foods that contain these carbohydrates.

Psychological Therapy

A meta-analysis of 25 randomized, controlled trials found that cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy reduced IBS symptoms immediately following these interventions.15In its 2009 position statement on IBS, the American College of Gastroenterology stated that psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy, dynamic psychotherapy, and hypnotherapy are more effective than placebo; therefore, retail clinicians may consider a psychiatric referral for patients with IBS and either significant stressors or a comorbid mental health condition.8

ICD-10 Codes

TheInternational Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision(ICD-10) codes for IBS include:

- K58.0: IBS with diarrhea

- K58.9: IBS without diarrhea

- F45.3: somatoform autonomic dysfunction (used for a psychogenic form of IBS)

Dr. Melissa DeCapua is a board-certified psychiatric nurse practitioner who graduated from Vanderbilt University. She has a background in child and adolescent psychiatry, as well as psychosomatic medicine. She is a strong advocate for empowering nurses, and she fiercely believes that nurses should play a pivotal role in shaping modern health care. For more about Dr. DeCapua, check out her blog at melissadecapua.com and follow her on Twitter @melissadecapua.

References

- Bijkerk CJ, de Wit NJ, Stalman WA, Knottnerus JA, Hoes AW, Muris JW. Irritable bowel syndrome in primary care: the patients’ and doctors’ views on symptoms, etiology and management.Can J Gastroenterol.2003;17(6):363-368.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Irritable bowel syndrome in adults: diagnosis and management. NICE guidelines CG61. https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG61. Published February 2008. Accessed January 4, 2016.

- Lovell RM, Ford AC. Effect of gender on prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis.Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(7):991-1000. doi:10.1038/ajg.2012.131.

- Agréus L, Svärdsudd K, Talley NJ, Jones MP, Tibblin G. Natural history of gastroesophageal reflux disease and functional abdominal disorders: a population-based study.Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(10):2905-2914.

- Bennett EJ, Tennant CC, Piesse C, Badcock CA, Kellow JE. Level of chronic life stress predicts clinical outcome in irritable bowel syndrome.Gut. 1998;43(2):256-261.

- Spiegel BM, Farid M, Esrailian E, Talley J, Chang L. Is irritable bowel syndrome a diagnosis of exclusion?: a survey of primary care providers, gastroenterologists, and IBS experts.Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(4):848-858. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.47.

- Thompson WG, Heaton KW, Smyth GT, Smyth C. Irritable bowel syndrome in general practice: prevalence, characteristics, and referral.Gut.2000;46(1):78-82.

- Brandt LJ, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein AE, et al; American College of Gastroenterology Task Force on Irritable Bowel Syndrome. An evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome.Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(Suppl 1):S1-35. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.122.

- Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders.Gastroenterology. 2006;130(5):1480-1491.

- Ruepert L, Quartero AO, de Wit NJ, et al. Bulking agents, antispasmodics and antidepressants for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome.Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;8(10):CD003460. doi: 10.1002/14651858

- Moayyedi P, Ford AC, Talley NJ, et al. The efficacy of probiotics in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review.Gut. 2010;59(3):325-332. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.

- Brenner DM, Moeller MJ, Chey WD, Schoenfeld PS. The utility of probiotics in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review.Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(4):1033-1049. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.25.

- Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, et al. Efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics in irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis.Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(10):1547-1561. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.202.

- Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome.Gastroenterology. 2014;146(1):67-75.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.09.046.

- Zijdenbos IL, de Wit NJ, van der Heijden GJ, Rubin G, Quartero AO. Psychological treatments for the management of irritable bowel syndrome.Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD006442. doi: 10.1002/14651858.

Knock Out Aches and Pains From Cold

October 30th 2019The symptoms associated with colds, most commonly congestion, coughing, sneezing, and sore throats, are the body's response when a virus exerts its effects on the immune system. Cold symptoms peak at about 1 to 2 days and last 7 to 10 days but can last up to 3 weeks.

COPD: Should a Clinician Treat or Refer?

October 27th 2019The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) defines the condition as follows: “COPD is a common, preventable, and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that is due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases.â€

Diabetic Ketoacidosis Is Preventable With Proper Treatment

October 24th 2019Cancer, diabetes, and heart disease account for a large portion of the $3.3 trillion annual US health care expenditures. In fact, 90% of these expenditures are due to chronic conditions. About 23 million people in the United States have diabetes, 7 million have undiagnosed diabetes, and 83 million have prediabetes.

What Are the Latest Influenza Vaccine Recommendations?

October 21st 2019Clinicians should recommend routine yearly influenza vaccinations for everyone 6 months or older who has no contraindications for the 2019-2020 influenza season starting at the end of October, according to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

What Is the Best Way to Treat Pharyngitis?

October 18th 2019There are many different causes of throat discomfort, but patients commonly associate a sore throat with an infection and may think that they need antibiotics. This unfortunately leads to unnecessary antibiotic prescribing when clinicians do not apply evidence-based practice.