Acid-Reducing Drugs: Basic Interactions

Approximately 60 million Americans experience heartburn once a month, and 15 million Americans suffer from it daily.

Approximately 60 million Americans experience heartburn once a month, and 15 million Americans suffer from it daily.1

Many prescription and OTC proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H

2

RAs), and antacids alleviate symptoms due to excess gastric acid.

Prescribing activity for gastric acid-reducing drugs has increased. In the ambulatory setting, PPI prescribing is a specific concern.2

A recent study’s results revealed that 62.9% of patients using PPIs had no gastrointestinal

(GI) complaints, GI diagnoses, or other

indicated reasons for use.2

Starting and discontinuing acid-suppressing drugs helps avoid drug interactions both now and later.

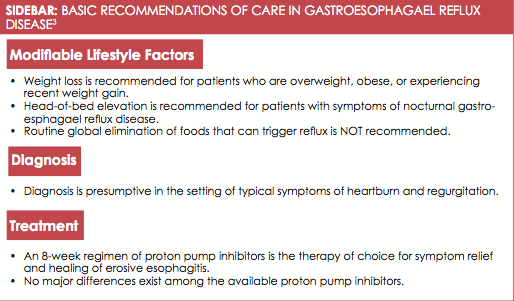

Clinical Guidelines

The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recently updated its guidelines covering the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).3

It indicates that PPIs provided faster, more complete heartburn relief than H

2

RAs.3

The guidelines recommend lifestyle interventions and PPIs as first-line treatments for GERD (see

Sidebar

3

).

Clinician Considerations

Clinicians must consider past medical history and potential drug—drug interactions (DDIs) before prescribing or recommending acid-reducing drugs. They should also conduct medication reconciliation, creating an accurate list of the patient’s medications (name, dosage, frequency, and route) by comparing the medical record to a list of medications obtained from a patient, hospital, or other provider.4

This helps identify potential DDIs and coordinates care among providers. Clinicians should also exercise caution when initiating acid-reducing drugs in patients who are on HIV regimens or take oral antineoplastics or in patients with chronic kidney disease.

Many HIV regimens depend on stomach pH for proper absorption. Therefore, adding an acid-reducing drug may alter absorption of the patient’s medication. For example, a DDI between the PPI lansoprazole and the protease-inhibitor (PI) atazanavir can lower atazanavir’s plasma concentration by more than 90%, leading to inadequate viral suppression.5,6

DDIs between PPIs and PIs can be more complex, too. For example, the PI nelfinavir requires low pH for solubility and is metabolized by cytochrome CYP2C19.6

The PPI omeprazole increases gastric pH and would theoretically lower nelfinavir plasma concentrations, but because omeprazole also inhibits CYP2C19, the effects counteract each other.6,7

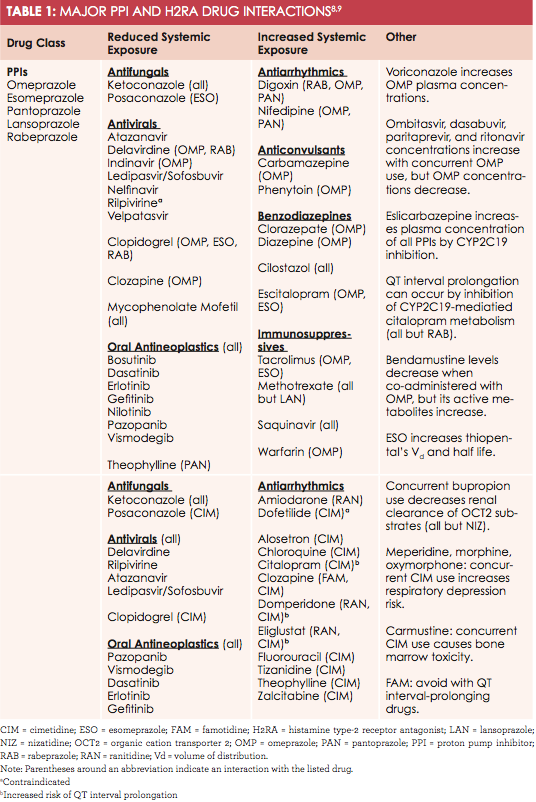

Table8,9

summarizes some major PPI and H

2

RA drug interactions.

pH-Dependent Interactions

Medications that require an acidic stomach pH are likely to interact with acid-reducing drugs. These include oral antineoplastics, antivirals, and antifungals. Most antivirals are HIV-specific; however, the hepatitis C antiviral ledipasvir-sofosbuvir interacts with all PPIs, H

2

RAs, and antacids. Many insurance companies refuse to cover a second round of this expensive medication ($1350 per dose8

) if the first round is unsuccessful. Complete, accurate medication reconciliation can avoid first-round failure.

Metabolic Interactions

Predominately metabolized by CYP2C19 and CYP3A4, H

2

RAs and PPIs have CYP-P450 interactions and may induce or inhibit these enzymes.

Consider this clinically notable interaction: clopidogrel is metabolized by CYP2C19 into active metabolites. Esomeprazole, omeprazole, and rabeprazole inhibit CYP2C19, reducing clopidogrel’s efficacy and increasing thrombosis and serious cardiovascular event risk.

Histamine-2 Receptor Antagonists

The H

2

RA famotidine prolongs QT interval. Mixing with other QT interval-prolonging drugs can cause fatal arrhythmias, like torsades de pointes. Therefore, avoid this combination. Cimetidine interacts with many drugs through CYP450, p-glycoprotein,

and various transporter systems. Concurrent use with meperidine, morphine, and oxymorphone can decrease opioid metabolism and precipitate respiratory depression.8,10

Antacids

Antacids have pH-dependent interactions similar to the PPIs and H

2

RAs

(see

Online Table 2

8

), but they have no known CYP interactions or metabolism/transporter effects. In addition to pH alterations, antacids’ metal ions chelate drugs and form insoluble complexes, preventing absorption.11

Patients with CKD should avoid aluminum- or magnesium-containing antacids; decreased renal function leads to ion accumulation, and possible hypermagnesemia or aluminum toxicity.12

OTC Considerations

In addition to interacting with prescription drugs, acid-reducing drugs can interact with OTC supplements, decreasing the absorption of multivitamins, minerals, and iron supplements

.

Conclusion

Retail health clinicians can use dosing strategies to mitigate acid-reducing drugs’ DDIs. For example, if a patient has heartburn while taking tetracycline, the patient could take an antacid 1 to 2 hours before the tetracycline and monitor for antibiotic effectiveness.8

Clinical drug-checker tools (eg, Micromedex) can also be used to screen for potential DDIs. Appropriate cessation of acid-reducing drug therapy will help prevent DDIs. Most importantly, medication reconciliation should be performed to screen for any DDIs that may be missed.

is a 2017 PharmD candidate at the University of Connecticut.

Thomas Walczyk

References

- American Gastroenterological Association. GERD. AGA website.gastro.org/patient-care/conditions-diseases/gerd. Accessed November 15, 2016.

- Rotman SR, Bishop TF. Proton pump inhibitor use in the U.S. ambulatory setting, 2002-2009.PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056060.

- Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease.Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(3):308-28. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.444.

- The National Learning Consortium. Medication reconciliation meaningful use toolkit. NLC website. healthit.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/privacy/medication-reconciliation-meaningful-use- toolkit.docx. Accessed November 15, 2016.

- Falcon RW, Kakuda TN. Drug interactions between HIV protease inhibitors and acid-reducing agents.Clin Pharmacokinet. 2008;47(2):75-89.

- Wedemeyer RS, Blume H. Pharmacokinetic drug interaction profiles of proton pump inhibitors: an update.Drug Saf. 2014;37(4):201-211. doi: 10.1007/s40264-014-0144-0.

- Fang AF, Damle BD, LaBadie RR, Crownover PH, Hewlett D Jr, Glue PW. Significant decrease in nelfinavir systemic exposure after omeprazole coadministration in healthy subjects.Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(1):42-50.

- Omeprazole, Esomeprazole, Pantoprazole, Lansoprazole, Rabeprazole, Famotidine, Ranitidine, Nizatidine, Cimeditine.Micromedex Solutions. Truven Health Analytics, Inc. Ann Arbor, MI. www.micromedexsolutions.com. Accessed November 15, 2016.

- Vanderhoff BT, Tahboub RM. Proton pump inhibitors: an update.Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(2):273-280.

- Guay DRP, Meatherall RC, Chalmers JL, Grahame GR. Cimetidine alters pethidine disposition in man.Br J Clin Pharmac. 1984;18(6):907-914.

- Calcium carbonate, aluminum hydroxide, magnesium hydroxide, sodium bicarbonate. In: Lexi-Comp OnlineTM, Lexi-Drugs OnlineTM. Hudson (OH): Lexi-Comp, Inc.; Accessed via UpToDate 2016 Nov

- Gugler R, Allgayer H. Effects of antacids on the clinical pharmacokinetics of drugs. An update.Clin Pharmacokinet. 1990;18(3):210-219.

- Paige NM, Nagami GT. The top 10 things nephrologists wish every primary care physician knew.Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(2):180-186. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60826-4.

Knock Out Aches and Pains From Cold

October 30th 2019The symptoms associated with colds, most commonly congestion, coughing, sneezing, and sore throats, are the body's response when a virus exerts its effects on the immune system. Cold symptoms peak at about 1 to 2 days and last 7 to 10 days but can last up to 3 weeks.

COPD: Should a Clinician Treat or Refer?

October 27th 2019The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) defines the condition as follows: “COPD is a common, preventable, and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that is due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases.â€

Diabetic Ketoacidosis Is Preventable With Proper Treatment

October 24th 2019Cancer, diabetes, and heart disease account for a large portion of the $3.3 trillion annual US health care expenditures. In fact, 90% of these expenditures are due to chronic conditions. About 23 million people in the United States have diabetes, 7 million have undiagnosed diabetes, and 83 million have prediabetes.

What Are the Latest Influenza Vaccine Recommendations?

October 21st 2019Clinicians should recommend routine yearly influenza vaccinations for everyone 6 months or older who has no contraindications for the 2019-2020 influenza season starting at the end of October, according to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

What Is the Best Way to Treat Pharyngitis?

October 18th 2019There are many different causes of throat discomfort, but patients commonly associate a sore throat with an infection and may think that they need antibiotics. This unfortunately leads to unnecessary antibiotic prescribing when clinicians do not apply evidence-based practice.