Curbing Childhood Obesity: What Clinicians Can Do

Childhood obesity is a serious problem in the United States.

Childhood obesity is a serious problem in the United States. More than 2 in 3 Americans are considered to be overweight or obese, and obesity is now the fastest-growing cause of disease and death in the country. The most recent data from the CDC indicate that approximately 17% (12.7 million) of children and adolescents aged 2 to 19 years are obese. The total health care cost of obesity in America was $117 billion in 2000 alone.1

The prevalence of obesity has more than doubled in younger children and quadrupled in adolescents over the past 30 years2:

- The percentage of obese children aged 6 to 11 years in the United States increased from 7% in 1980 to nearly 18% in 2012.

- The percentage of obese adolescents aged 12 to 19 years increased from 5% to nearly 21% over the same period.

The good news is that the prevalence of obesity among children aged 2 to 5 years decreased significantly from 13.9% in 2003—2004 to 8.4% in 2011–2012.1

Obesity is now the most prevalent nutritional disease of children and adolescents in the United States. Although obesity-associated morbidity is more common in adults, significant consequences of obesity, as well as the antecedents of adult disease, are seen in obese children and adolescents. This review considers the adverse effects of obesity in children and adolescents and outlines what retail clinicians can do to ameliorate the problem.

Obesity-Related Health Risks

Obesity in childhood can cause a wide range of serious complications. Obese youth are at increased risk for multiple health concerns related to cardiovascular disease, such as high blood pressure and high cholesterol. Obesity can affect children socially (eg, stigmatization) and emotionally (eg, low self-esteem). According to the Harvard School of Public Health, obesity is harmful to children’s heart and lungs, bones and muscles, kidneys and digestive tract, and the hormones that control blood sugar and puberty.3

Kids who continue to be overweight are at increased risk for remaining overweight as adults. As a result, their chance for illnesses, diseases, and disability could increase later in life.

Obesity Epidemiology and Causative Factors

How does someone become overweight or obese? The answer is simple: by consuming too many calories in conjunction with expending too little energy to burn off those excess calories. Obesity in children is defined as a body mass index (BMI) at or above the 95th percentile compared with children of the same age and sex.1

Advances in modern technology have led to the availability of more forms of children’s entertainment, such as handheld electronics, video games, and computers. This may result in a decrease of the overall time children spend expending daily calories. The subsequent weight gain among children reinforces the risk for possible heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and other chronic conditions.

Obesity is more common among children and adolescents of certain racial and ethnic groups. In 2011—2012, the prevalence was higher among Hispanic and non-Hispanic black children (22.4% and 20.2%, respectively) than among non-Hispanic white children (14.1%). Similarly, prevalence was lower in non-Hispanic Asian youth (8.6%) than in youth who were non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, or Hispanic.1

Obesity in children is related to the education level of the head of the family. Between 1999 and 2010, the prevalence of obesity among children whose adult head of household completed college was approximately half that of those whose adult head of household did not complete high school (9% vs 19% among girls; 11% vs 21% among boys). Parental income level impacts childhood obesity, as well. The prevalence of obesity among children aged 2 to 4 years from low-income households in 2011 varied by levels of income-to-poverty ratio, which is a measure of household income. Obesity prevalence was highest among children in families with an income-to-poverty ratio of 100% or less (household income at or below the poverty threshold) and lowest in those with an income-to-poverty ratio of 131% or higher (greater household income above the poverty threshold).1

Obesity Care Strategy

The obesity epidemic among today’s youth continues to escalate. Although research results have provided new insights into the physiologic basis of body weight regulation, treatment for childhood obesity remains difficult and largely ineffective. Therefore, prevention is the most feasible option for curbing this childhood epidemic. Even current treatment practices are largely aimed at bringing the problem under control instead of effecting a cure. The primary goal in combating childhood obesity is to achieve an energy balance that can be maintained throughout the child’s lifespan.

Childhood obesity is a complex problem that requires a multifaceted approach. Policymakers, state and local organizations, business and community leaders, schools, childcare and health care professionals, and other stakeholders must work together to create an environment that supports a healthy lifestyle. State and local resources are available to help disseminate consistent public health recommendations and evidence-based practices for state, local, territorial, and tribal public health organizations, grantees, and practitioners.

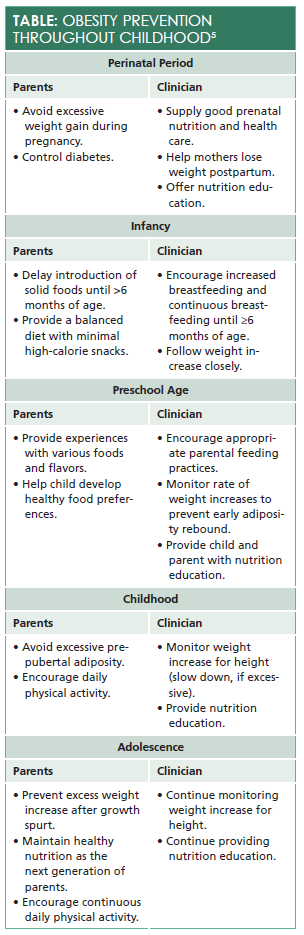

Knowing the BMI, achieving and maintaining a healthy weight, and getting regular physical activity are required to prevent overweight and obesity. TheTable4outlines ways in which parents and clinicians can help children achieve these goals.

The Clinician’s Role

Clinicians play an integral role in educating patients and their parents or caregivers about the dangers of obesity and how to prevent it. In fact, clinicians are sometimes the first to inform parents that their child is overweight or obese. At each and every visit, the first objective measure obtained is the height and weight of the child. Parents should be aware when their child’s BMI level is not appropriate for his or her age.

Clinicians need to take into account the challenges low-income families face, as children’s nutritional and physical habits are highly influenced by their school, home, and community environment. Clinicians need to demonstrate general concern about patients and their well-being, as well as the knowledge of the parents. Some general dietary recommendations clinicians can discuss with parents include increasing the child’s consumption of fruits and vegetables, legumes, whole grains, and nuts; limiting energy intake from total fats and shift fat consumption away from saturated fats to unsaturated fats; and limiting sugar intake.

Another vital recommendation is to increase physical activity. Clinicians should advise parents to encourage their children to have at least 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity each day. Healthy childhood habits, like those instilled by playing sports, could foster a lifetime of healthy behaviors. No one can sustain their weight for any length of time without regular physical activity, but kids don’t need to run marathons; they simply need to play. Besides the physical benefits, such as improved bone and muscle strength, exercise has been shown to improve one’s emotional and psychological state. It is vital that clinicians address this issue at the first patient visit.

Weight-loss medications may help adult obese patients curb the appetite or control weight gain/loss, but few are approved for use in children. Therefore, encouraging lifestyle modifications of eating healthier foods and increasing physical activity will contribute more to the prevention of childhood obesity.

The ultimate goal for clinicians is to inspire and reassure parents that they can help prevent unhealthy habits in their children. To that end, clinicians can suggest the following activities:

- Push for healthier foods and snacks offered in school cafeterias and vending machines.

- Have children partake in growing and/or buying the foods they eat (eg, start a backyard garden).

- Involve kids in making their own food choices.

- Participate in family activities such as walks after dinner or playing at the park.

Finally, educate parents to be role models. If parents accept and embrace healthy eating and exercise practices for themselves, their children tend to adopt the same behaviors.

Kathy Veenendaalis a board-certified family nurse practitioner with 17 years of health care experience. She received her bachelor of science in nursing from the University of Illinois at Chicago and her master of science in nursing from Northern Illinois University. Her background includes emergency medicine, cardiology, and family practice. Currently, Kathy is a clinical educator for Walgreens Healthcare Clinics. She is passionate about and dedicated to improving health care for patients. Her career goal is to enhance health care access.

References

- Childhood obesity facts. CDC website. cdc.gov/obesity/data/childhood.html. Updated June 19, 2015. Accessed May 11, 2016.

- Childhood obesity facts. CDC website. cdc.gov/healthyschools/obesity/facts.htm. Updated August 27, 2015. Accessed May 11, 2016.

- Child obesity. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health website. hsph.harvard.edu/obesity-prevention-source/obesity-trends/global-obesity-trends-in-children. Accessed May 11, 2016.

- Deckelbaum RJ, Williams CL. Childhood obesity: the health issue.Obes Res. 2001;9:239S-243S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.125.

Knock Out Aches and Pains From Cold

October 30th 2019The symptoms associated with colds, most commonly congestion, coughing, sneezing, and sore throats, are the body's response when a virus exerts its effects on the immune system. Cold symptoms peak at about 1 to 2 days and last 7 to 10 days but can last up to 3 weeks.

COPD: Should a Clinician Treat or Refer?

October 27th 2019The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) defines the condition as follows: “COPD is a common, preventable, and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that is due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases.â€

Diabetic Ketoacidosis Is Preventable With Proper Treatment

October 24th 2019Cancer, diabetes, and heart disease account for a large portion of the $3.3 trillion annual US health care expenditures. In fact, 90% of these expenditures are due to chronic conditions. About 23 million people in the United States have diabetes, 7 million have undiagnosed diabetes, and 83 million have prediabetes.

What Are the Latest Influenza Vaccine Recommendations?

October 21st 2019Clinicians should recommend routine yearly influenza vaccinations for everyone 6 months or older who has no contraindications for the 2019-2020 influenza season starting at the end of October, according to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

What Is the Best Way to Treat Pharyngitis?

October 18th 2019There are many different causes of throat discomfort, but patients commonly associate a sore throat with an infection and may think that they need antibiotics. This unfortunately leads to unnecessary antibiotic prescribing when clinicians do not apply evidence-based practice.